Christopher Andreae

As W.S. Gilbert put it: "When everyone is somebody/ Then no-one's anybody." This makes more sense to me than Warhol's "15 minutes of fame" for each of us. I do think that, generally, the celebrity thing has got a bit out of hand these days.

So the modest hope for this website is that it might share interests with anyone who wanders this way.

Art has been an abiding interest, a (quite intense) pre-occupation. I don't believe in espousing traditional or modern to the exclusion of each other or writing off, say, abstract art in favour of figurative, or conceptual in favour of perceptual. Such divisions are pure nonsense in an art world where anything goes (or should).

Of course I have favourite artists – really far too many to list here – but I might mention Morandi, Seurat, Vermeer, Matisse, Degas, Gris, Samuel Palmer, Edward Hopper, John Sell Cotman, Christopher Wood, Joan Eardley, Mary Newcomb . . . . and of course there are artists who are the ever fresh meat and drink of art history: Piero della Francesca, Rembrandt, Manet, Cezanne, Constable, Picasso, Van Gogh . . . . In spite of the vast amount of analysis and admiration expended on such artists, they remain wonderfully inexplicable.

I do greatly enjoy the process of trying to grasp the individual "language" of an artist. Take for example Philip Reeves, about whom I am writing a book - he deserves one - his work may seem entirely "abstract" at first sight, but it turns out not to be. It does, however, require a leap of the imagination to enter his precise and subtle "world" – his landscape of colour and shape, dark and light, overlap and underlap, edge and contour – to appreciate what he is about. Here is art that needs time and familiarity for it to grow on you. It is not the work of a moment, and can't be "seen" in a moment.

Writing has been my chief occupation. It's one of those pursuits that is most rewarding when it is over. It's also a task that is quite difficult to get started. So, really, the only passably sensible advice one can offer a would-be writer is: "Don't" (unless you just can't help it.) But if you do find yourself, by default, caught up in this dubious pastime, then something Michelle Dovey, a contemporary artist, has to say about her work is worth heeding. When painting out of doors, she begins with long contemplation and observation of the multiple facets of her chosen subject – in this case trees. Then insects start to get stuck in her paint and the canvas is being blown around. "I'm getting cold," she writes, "and there is the job of getting it all down. I realise I am going to have to paint like the wind and stop thinking about it. (My italics). So – write like the wind and stop thinking about it.

One thing I much enjoy is giving illustrated talks. I give them to National Association of Decorative & Fine Arts Societies, art clubs, art galleries, rotary lunches and libraries. Some people flatteringly upgrade these efforts to "lectures", others charmingly call them "chats". They probably lie somewhere between the two extremes. Certainly they aren't overwhelmingly formal. A talk I gave recently at the auctioneers Lyon and Turnbull, in Edinburgh, was described by a listener afterwards, appreciatively I think, as "informed rambling."

Who was it that said the art of acting is to stop people in the audience coughing? In my talks I try to stop people doing either that or falling asleep – people who, understandably comfortable in the warmth and darkness, usually just after lunch or supper, look suspiciously like dozing off. They have my sympathy but I try to rouse them with a sudden change of pace or volume or a joke. However, a sporadic mobile can be a help in this endeavour. One sounding out half way through a recent talk proved effective. It even woke me up. I immediately thought it was mine and fumbled inconclusively in various pockets. But afterwards a very honest lady came up and apologised. I could say truthfully that I hadn't minded at all.

So far my talks have been about the artists who have been the subjects of my books: Mary Newcomb, Mary Fedden, Winifred Nicholson and Joan Eardley. The most recent, my talks on Eardley, have been particularly well attended. Of course this is down to the remarkably popular, touching and communicative character of her art.

The books I've compiled and written do seem to give pleasure to others and this in turn gives me great pleasure. But such rewards from the books emerge slowly and even obliquely. The talks, on the other hand, elicit immediate responses from audiences and this gives one a special kick.

Now and then someone admits that they have actually read one of the books from start to finish. To me this is amazing; art books seem more likely to be looked at – they are essentially, after all, picture books. Words can even detract from experiencing a painting or drawing to the full. I try to avoid "art speak". I have been much helped in this by editors.

Collecting, certainly a pretentious name for my modest activity, is definitely a sideline and has often been generated by my writing. Serious collecting would make one obsessively possessive, but the monetary value of works (which doesn’t inevitably go up!) has nothing to do with their real worth. Close appreciation has much more to do with it. Greatly appreciated pictures have come my way through the generosity of the artists I have written about. Mary Newcomb and Mary Fedden, for instance. Andrew Nicholson, youngest child of Ben and Winifred Nicholson, very kindly offered me a choice: one of two paintings by his mother. Another painting by Winifred came directly from her.

The first work I ever bought was a small rich print of woodland tree trunks by Valerie Thornton, a wonderful piece of work by this strong, individualistic etcher, whose reputation today seems to have waned unjustifiably. I remember the trepidation I felt sitting in the car park in Farnham wondering what on earth my father would say about such shameless extravagance. The etching cost 6 guineas. Oddly, I do not remember Dad's reaction! Perhaps I hid it from him. I have never regretted buying it.

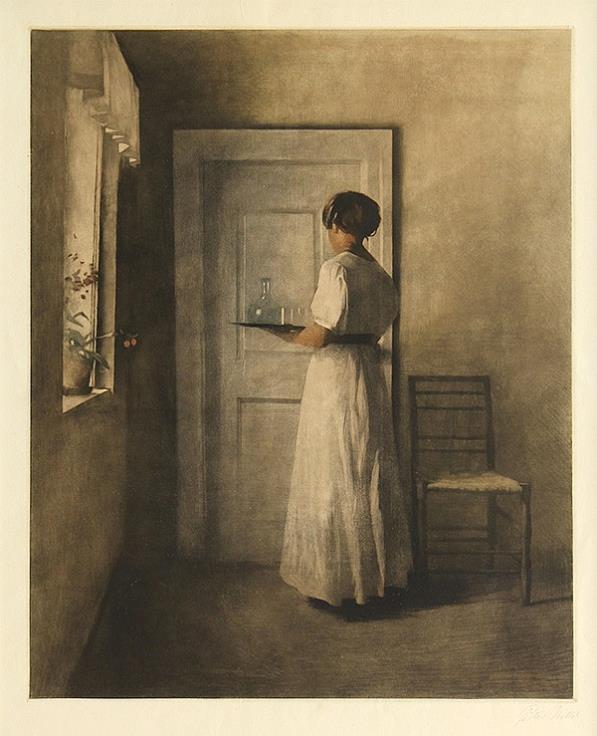

A similar excitement attended buying, in the early 1960s, a small abstract black steel sculpture by Brian Wall. Drawings and a painting by the Scottish artist Jack Knox have been no less exciting. A more traditional work we have is a mezzotint by the Danish artist Peter Ilsted called "Girl with a Tray" of 1915.

Other favourites include a graphite drawing of some cows by Henryk Gotlib (a Polish artist who settled in England at the outbreak of WWII); a marvellous accumulation of small pastels by the sculptor David Nash sent at Christmas and a pastel of clouds by his wife, Claire Langdown; an etching by Samuel Palmer; a print by Sonia Delaunay; a painting made of pure pigment by Natvar Bhavsar. And a bronze of a seated dog by Shona Kinloch.

Another Polish artist, Josef Herman, particularly his paintings of coal miners.

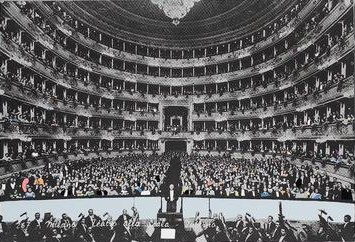

A print of La Scala by Richard Hamilton is a particular favourite of my wife.

And a favourite of mine by the same father of "Pop Art": his aquatint, "Homage to Seghers", in honour of a Hercules Seghers (17th century) print of books piled on top of each other.

Several lovely ceramic items have come our way, two exquisite bowls by the potter Jennifer Lee at the top of the list, and a small, sensitive, unpretentious cup and saucer made by Lucie Rie, and a splendid, round-bellied pre-Columbian ceramic dog. Two black and white linocuts by the African artist John Muafangejo never stop fascinating me. The subjects of our two are "the fat pigs" and "a rich man".

More eccentric collecting includes rather a large number of old Victorian ink bottles – this sort of thing:

"Inks" come in an enormous variety of shapes. They are usually aqua, blue or green in colour. They can be barrel-shaped, shaped like cottages, boats, barrels, they can be octagonal, square, round and three-sided, fluted, embossed. Some are common and cheap, but others very rare and pricey,

Cap badges are also colourful and fun to collect, and won’t break the bank. The ones I go for are like this one:

I'm not sure what started me collecting cap badges. I’ve never worn a cap (except perhaps at school), and my badges (which are either advertising petrol or fizzy drinks, but are not military) are just displayed by being stuck to the wall - like little pop art images really.

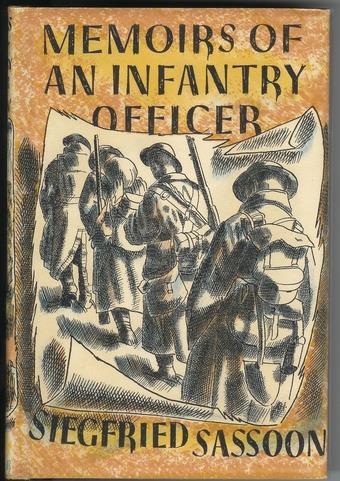

Illustrated books are for me an extension of my love of paintings and drawings, and I might mention just three superb but quite different illustrators I can't resist. They are Brian Wildsmith, Clare Leighton, and Barnett Freedman. Freedman’s subtle illustrations for Siegfried Sassoon’s "Memoirs of an Infantry Officer".

Wildsmith's rich, free, rainbow spectrum colourful illustrations for children's books.

Leighton’s stunningly deep blacks and sharp whites in her wood engravings.

My own efforts at painting and drawing, over many years, are embarrassing by comparison, but with all due immodesty, here are some. I am including them here only because sometimes, after a talk, somebody in the audience will ask if I paint. I generally say that yes, I do, and that it certainly helps in my writing about art. So here goes. All these have been photographed by Andy Phillipson.